THE HUNDREDS BLOGTalking Identity Politics & Race with the Creators of Ori Inu: In Search of Self (2016)

It is presidential election time in the United States, a time when any and every issue psychologically divides the American masses. This season in particular, no subject seems to be more prevalent, and equally as sensitive, as the elephant in the room named Race. Some of it is due to the unprecedented circumstances of Barack Obama’s presidency—the nation’s first black commander in chief. Some of it is also due to a very deep, often downplayed, national history of genocide, colonialism, and racial injustice. All of it, in turn, has reached a trending critical mass—the likes of which we’ve never seen in our newly Internet-driven lives.

Not only is the present-day conversation about race in America at center stage right now, it’s also all over social media and the Internet—a double-edged sword of sorts in regards to perspective versus reality. Though the past eight years have continued to pen bleak chapters in the racial narrative, the reality is that white supremacy, systematic oppression, racial profiling, mass incarceration, and the killing of unarmed black civilians are not a new phenomena in the United States. However, if the timelines, feeds, and general social media uproar tell it, the unrest has been carried into a much noisier arena of debate, where even the most well-intended ideas and opinions can drown in a sea of digital cynicism—or worse yet: become hashtags without action.

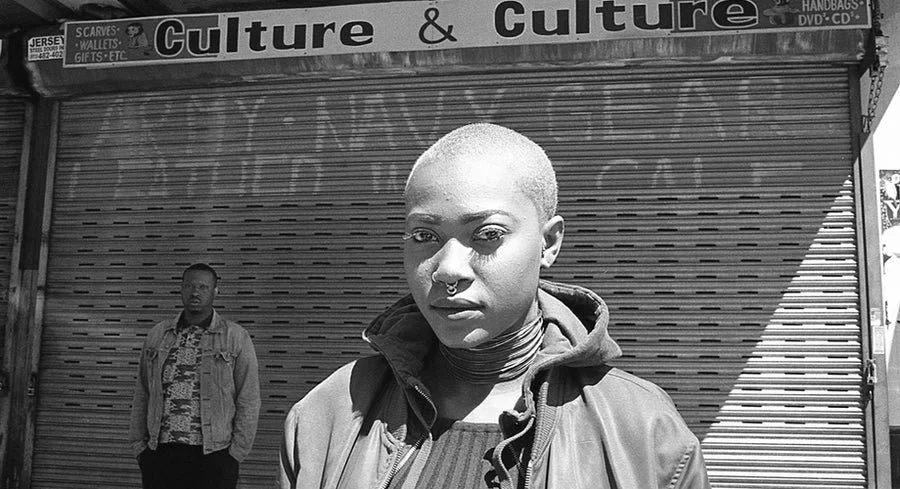

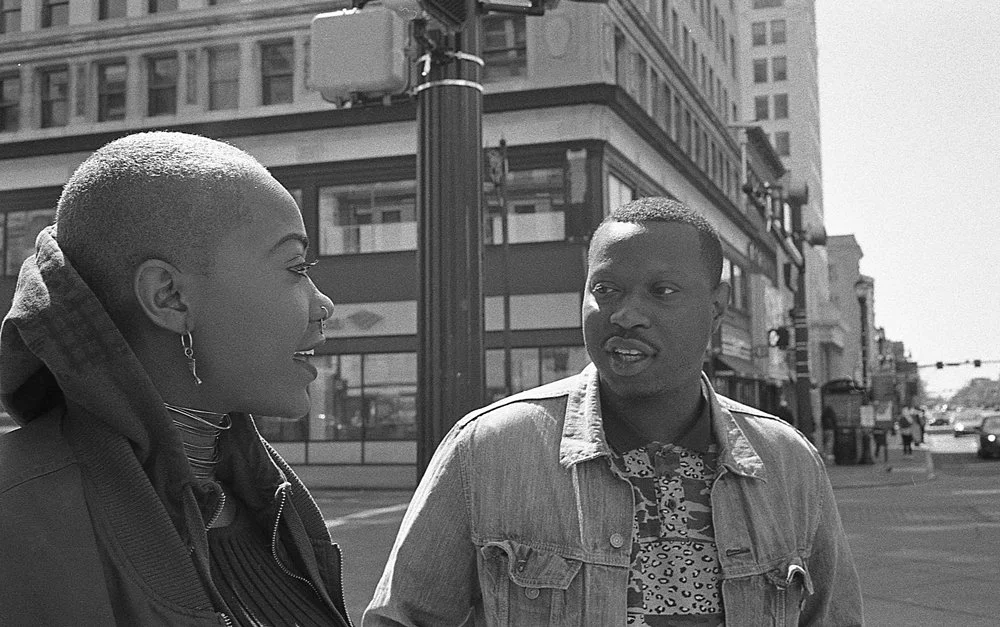

When I spoke to sister and brother duo, Chelsea and Emann Odufu, about their new film, Ori Inu: In Search Of Self (a film very much about a history of racial and religious persecution), I learned that, just like with the current political climate, the hashtag-ization of culture can also be a very polarizing place for art and activism. Refreshingly, amidst all of the digital debate surrounding everything from #OscarsSoWhite and #BlackLivesMatter, to #BlackGirlMagic and Beyonce’s controversial Superbowl #Formation this year, I was happily surprised to hear Chelsea and Emann refer to the message behind their work as spiritual fluidity. Yes, fluidity—not polarity. Not black. Not white. Not this or that, but rather, how the culmination of particular histories can connect any one of us to the spiritual roots of all of us. Past, present, and Afrofuturist ideals regarding art, music, and activism also took shape as the directing and producing siblings described their upbringing and journeys toward racial and spiritual identity. Theirs is a refreshing approach to black empowerment—a humbling beacon of inclusivity and community-building during a time of much division and individualism.

RAINEY CRUZ: Where were you raised?

CHELSEA ODUFU: We both grew up in Newark, New Jersey. We’ve lived here all of our lives.

What was it like growing up there?

C: Growing up in Newark definitely has a stigma and stereotype. We never lived that dominant and negative view. We always looked outward and into the city to define who we are. There was always this tension between African-Americans and Africans that I saw or felt. I would get made fun of a lot for my last name and being African. It always put my blackness in a weird position.

Tell me about your family and ethnicity.

C: Our parents are from Guyana and Nigeria. Our mother raised us as a single parent, so we were predominantly raised in a Guyanese household. We identified with being Caribbean. It was something that I really embraced.

How do you identify with your ethnicities?

C: I do feel that we are Caribbean and we are Nigerian, but we’re also American. We are very much that narrative of an immigrant family, but we’re second generation Americans. It then becomes a question of black identity here and navigating the Diasporic experience. It’s a question of whether we assimilate to Western ideals or not. It’s something that we always deal with.

EMANN ODUFU: You feel like an outsider. You don’t feel 100% American, but because we’re half Guyanese and half Nigerian, we also don’t feel like we’re 100% African. It’s this idea of being part of everything and simultaneously being outside of everything.

What kind of cultural and creative influence did your mom and family play in your lives?

E: Our mom really exposed us to a lot of art. She would play all this Jazz, like Grover Washington and Down To The Bone. It was constantly present. When I was in high school, we were also able to visit the Prado Museum in Spain. I think that really helped gives us our world view. We were from Newark, but we weren’t really thinking about Newark. Chelsea was traveling too and living in Italy when she was 15. We were very much raised as an international family. We were always thinking about things bigger than our surroundings. That played a huge role in us becoming artists and thinking about larger issues and platforms.

Tell me about your relationship as brother and sister and how that relates working together.

C: I think my brother and I have a pretty close relationship. When we were younger, we used to play music together. This was around when I was 12. We would perform at different places and events like street festivals. We never formally discussed making art and developing a family company per se, but it has really worked out that way. I believe in him and we’re pushing each other because we really want to make this happen and touch people. It’s a super dope dynamic.

E: I agree completely. Definitely.

How did the idea for Ori Inu: In Search of Self come about?

C: This started off as my senior thesis film project for undergraduate film at NYU. My scope wasn’t to only make a student film and try to submit it to festivals. We understood that this is an experience that we need to talk about because this is something that we’re actually going through. Spirituality even lies in the Black Lives Matter narrative. Black spirituality matters. We wanted to create a dialogue among people from here, to Brazil, to Africa, and all places.

Tell me about your spiritual upbringing and how making this film has propelled your journey?

C: My brother has really influenced my spirituality and we grew up in a very spiritually non-traditional household. A lot of my family is Jehovah’s Witness, I went to Catholic school, I had friends who practiced African spirituality, and I used to go to Hindu temples. I feel like my knowledge of spirituality is very fluid in general.

E: I think that because of my Christian upbringing, a lot of spirituality outside of that was stigmatized. Even stuff like ancestor worship was looked down upon. I grew up countering the brainwashing of Christianity. I really had to ask the question, “If my ancestors were not practicing Christians, were they bad people?”

True Christianity is about love, understanding, and acceptance. That’s what we’re trying to do with this film. For me specifically, I’m trying to ask why can’t Christianity be more open to other types of religions and beliefs? Isn’t showing love to your fellow human beings, being like Jesus? It pushed me. Even when I was writing the script, things would feel weird. I wouldn’t know what it really was, but I knew it was about being open to other people and open to the world.

Can you explain the idea of spiritual fluidity and how it relates to the history that is explained in the film?

E: One thing that has always fascinated me is how similar all religions are. We were told that African spirituality and Christianity were so different, but you can find ways to connect them. For example, the synchronicity of saints and deities are everywhere from Haiti to Mexico. They would equate a lot of the Christian saints with the African orishas. These things were going on at the same time. People would be into their Christianity and still into their African spirituality as well.

How is this concept of fluidity tied to Afrofuturism?

E: In connection to Afrofuturism, I think that it is this idea of bringing together all of these different concepts of spirituality into a new and neo form. I think that’s what our film is really about. We’re celebrating the existence of non-Western ideologies, the idea that something can be different but also the same at its core.

What have been some of the reactions to the film’s trailer and your engagement with audiences?

C: I went to talk at Trinity College and there was this 75 year-old white woman who told me she questions whether her own religious tradition of church was really valid for her. The conflict between religion and spirituality is also a concept that people don’t often talk about. It crosses racial barriers.

People might think that this is only a black film or that this can only touch a very specific set of people who have a connection to African history. Yes, this film may be targeting that experience as a healing process for people of the Diaspora, but the power of people trying to find themselves is a universal thing.

How important was is it for you to accurately portray the Candomblé religion in this film without romanticizing it?

C: Because we knew that we were essentially outsiders making a film about a spirituality that resonated with us, it was super important for us to make sure our film created an accurate depiction. We were extremely aware of the stigmas placed on traditional African religions and wanted to ensure that our film showed an alternate perspective.

How did you gather information and research?

C: We did a lot of online and book research, but as we got deeper into the creation process, we began to have a lot of unplanned personal encounters with practitioners of similar religions. We ran into an Ifa priest in Brooklyn, Spiritual Baptist priestess in Trinidad, and Santeria practitioners in Miami. Each of our encounters and discussions helped to shape the narrative.

What kinds of spiritual encounters did you come across during travel for the film?

C: When we were in Trinidad location scouting, a woman in all yellow approached us at the mouth of a river and asked us what we were doing there. It was obvious that she had just completed a river cleansing. We told her about how we were searching for a beach location for our shoot. She told us that we need to go shoot at the specific place where the “sisters” meet, where the ocean and the river meet. The place that we came upon was exactly what we needed.

What was the significance of Fela Kuti, filming at The Shrine in Harlem, and featuring some modern-day African music acts in Ori Inu?

C: Harlem has a huge African community, but I just didn’t know that it had this venue that was so African-themed, with all the albums on the walls. It was so beautiful to be in that space, a place that embraces African ancestry, spirituality, and music. I think it’s a very Afrofuturistic place. I thought it would be a perfect location to shoot in. Abdul, the owner, was very cool and they really supported us. We got Les Nubians and Oshun to perform there, which was awesome. It completely embodied what we imagined for the scene.

E: Fela [Kuti] was so dope because of his story and how he created a whole musical genre. He was a huge inspiration for me and someone that got me really thinking about African spirituality and its connection to music. That’s also why we made music such a big part of the film. We wanted to show that connection that we take in on a daily basis. I really think that you can classify even certain trap music as being able to touch the soul. I consider a lot of music and pop culture as part of African spirituality.

Was hip-hop an influence or connection to spirituality as well?

E: Hip-hop is definitely what started me on my spiritual journey. When you’re coming up you’re learning about the Five Percenters and Wu-Tang. I look at hip hop as a religion in itself. That’s why you have artists like Kanye West calling themselves “Yeezus” now and artists like Erykah Badu and her album “New Amerykah” where she’s talking about hip-hop being bigger than the government and religion.

How has working on Ori Inu affected your outlook on spirituality in others?

C: We realized how many other people actually practice African spirituality. People would come to castings and tell us that they spoke to their spiritual leaders and how, even if they didn’t get the role, they wanted to send many blessings. I would’ve never imagined. So I realized how connected I am and how many other people are and don’t talk about it.

We would visit schools like Yale, and after our talks people would tell us how they were interested in spirituality, and if we could tell them about our journey. We’re not spiritual gurus but we can tell you about how this is our experience. It’s just interesting how this film has given other people who don’t know us, a comfortable space to talk about it.

You both consider yourselves to be art activists. Can you define this and its relation to Ori Inu?

E: Art activism is what we’ve been doing at the schools in our tours and reaching the youth. Fostering conversation among them, the future, and making them look at the world in a different way. It’s important because this is what’s going to spark the conversations that are not happening and need to be happening. As an artist it’s important to make sure you are reaching the people and getting the right messages across.

Images are a way to communicate what you cannot say. There are a lot of people who may not relate to a speech or book, but see art that reaches them in a different way. It’s kind of like what Chris Rock did at the Oscars. He was telling these jokes and talking about a lot of poignant issues. I feel like art is a strong tool to discuss the “unspeakable” things in our society that are still taboo.

C: For us, it’s about making sure that our stuff is really grounded and giving a voice to people that don’t necessarily have voices. We make sure to include discussion. We’ve been having workshops about identity, diversity, and representation as part of our tour across different schools like Yale, Barnard, Wesleyan, and Vassar. We’re making sure that there’s a second step towards promoting further conversation about reflection and critical thinking regarding what this all means.

How do you feel about the “trendiness” of blackness or black history in popular culture?

C: A lot of concepts about “blackness” or catch phrases like “black girl magic” are being commodified by white popular culture. Which, for me, makes these things lose their real value or purpose for black people. Lyric, one of the film’s actors, is from Newark too, and she’s growing up in the era of “black girl magic” and not being broken. It’s also important to embrace that and the actual healing elements that are happening.

It’s important to see stories or narratives about slavery and history, but do we as a people now become desensitized from the struggle because it’s so popular? That’s scary to me. We have shows like “Underground” now and we’ve seen so many slavery narratives that now we question whether it’s just entertainment or if people are going to give it more thought after that.

What has been the most difficult part of creating Ori Inu?

C: For the most part, we have just been a really small team trying to do something really large. I think that was/is the hardest thing. We want to do so much with this film but it’s really just me, my brother, and my mom that are consistently devoted. We’ve really had to hustle and this whole project has been a huge learning curve for us. Of course, we had a crew every time we went to shoot, and I don’t want to discredit our Associate Producer, Ashley Webster, and the entire team, which was amazing!

What was it like to cast award-winning talent like Tonya Pickens and other important roles for the film? How did they all relate to the project?

C: Tonya was one of the first people, in terms of big name talent, to support us. There was a kid in my NYU class that had casted a big name and it inspired me to do the same. Tonya was very moved by the script and thought that we had a lot of potential. It’s the same thing that happened with Les Nubians. They thought it was great and wanted to meet out in Brooklyn. From the very start, we had people telling us that what we had was very strong and it was why they wanted to be a part of it.

Tre’von and Helen both went to NYU with me, so this was also a graduating and final project for them. I feel like they were both also having their own individual spiritual journeys too. Helen would talk about being Ethiopian and American and growing up in Philly—her own experience with that. Tre’von grew up in a very religious household and also had his own interesting relationship with Christianity.

I think that everybody agreed that the film brought together a wonderful cast. Folasade Adeoso, the model, was also part of the film, in addition to Trae Harris, who’s in Newlyweeds.

How fluid was the cast and staff itself?

C: If you see photos of everybody behind the scenes, we’re all Afrocentric. The film crew was a very diverse crew, and that was very interesting and multicultural in itself. And how these spiritual representations were not only in African culture, but other cultures also connected with them or had questions about them. It brought it all together in a very cool way.

What does this film mean to all of you?

C: This film was a physical manifestation of our journeys. There may have been things that had already occurred to us spiritually, but physically what grounded the experiences was making the film.

What has making Ori Inu and learning more about your African roots taught you about your own search for self?

E: Growing up, I always thought that Africa and the Caribbean were worlds apart. But when making this film, we discovered how interconnected everything was. Traditions like Carnival in the Caribbean have African origins. Even when we went to Trinidad, we realized that the same religion of Candomblé and the belief in deities like Yemaya was also connected to the religion of Yoruban tribes in Nigeria. It was a lesson on how African culture as a whole translated itself in other places.

What’s in store for the future of Ori Inu and your art activism?

C: Being from Newark, New Jersey, it’s important for us to give back. We want to go on a high school tour. We’re planning to do workshops with schools based on their needs. What are students facing? Where is the tension? Art Activism is about unity and enabling conversations about our experiences in being hurt by people that do or don’t look like us.

Sacha Jenkins On His Must-See Hip-Hop Fashion Documentary “Fresh Dressed” (2015)

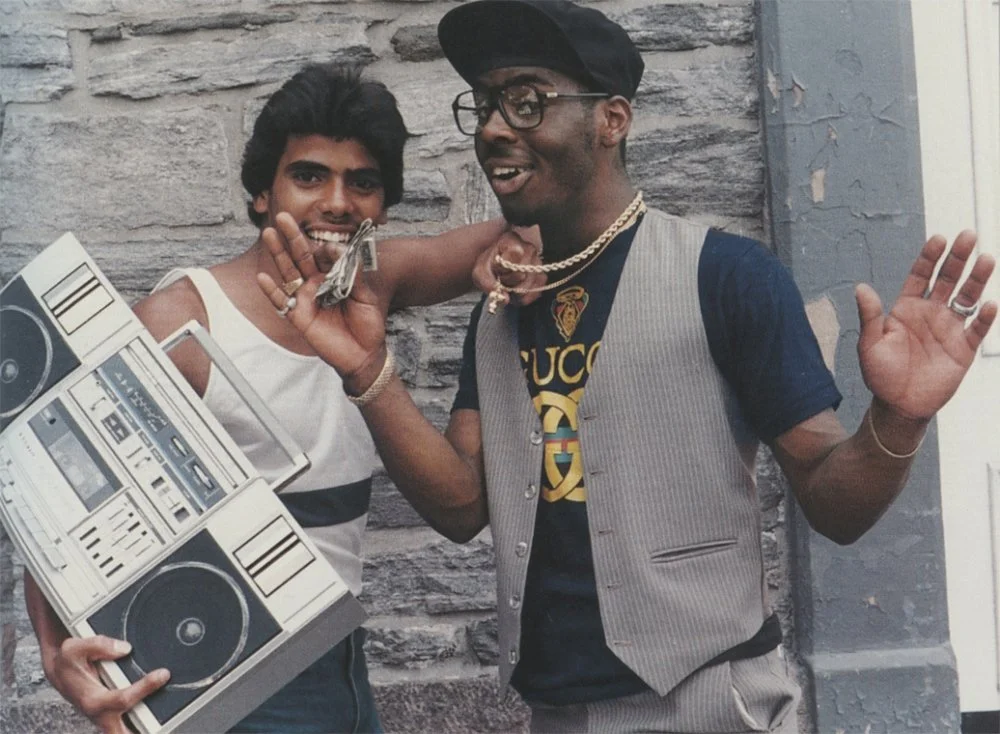

We interviewed Sacha Jenkins back in January about his powerful documentary on hip-hop fashion, Fresh Dressed, when it was screening at Sundance. Now that the film is showing in theaters and available for streaming and purchase online, we though it was a great time to reshare this illuminating interview.

“Ask and you shall receive,” goes the saying. “If it’s meant to be, it will work out,” is another one of those reassuring Zen phrases. I’ll be honest – I definitely went to work on this assignment by keeping these ideas and the Universe’s benevolent hand in mind. Not because it would be impossible to interview friend and former coworker Sacha “SHR” Jenkins about his upcoming Sundance film, but because our insanely conflicting schedules would need some sort of blessing from above to coincide. This said, it did happen. Just a few hours before SHR was scheduled to board his flight out to Utah, in fact, I was welcomed into his abode for our talk. I was convinced that the higher powers were indeed at work. The prior week-and-a-half’s texts, emails, phone calls, and intentions, most importantly, had all culminated into this one window of time and peace with the director and historian. I was honored. Sacha was poised, grabbing hold of his nearby electric guitar and strumming while I gathered myself and my interview questions. In less than 24 hours, he would be premiering his brand new, fashion-driven, hip-hop documentary, Fresh Dressed, at the Sundance Film Festival – a very big feature and deal supported by both Mass Appeal and CNN Films.

But for me, perhaps more important than its premiere, was what this film meant to Sacha and what it would mean for fans of hip-hop culture and direct descendants of its history, such as myself. The result of our sit-down was an intimate conversation about the power of people and their journeys, told or untold. The Universe truly is at work. So is the legacy of the transformative spirit of hip-hop fashion.

RAINEY CRUZ: How was the idea for Fresh Dressed originally conceived?

SACHA JENKINS: I felt [Fresh Dressed] was an interesting way to tell the overall story of hip-hop, which is bigger than the music itself. It’s really about society, the environment, and the climate that created or inspired young people to do what they wound up doing. So many stories have been told about hip-hop, but not from the perspective of fashion.

Describe the attitude or approach required for you to work on longterm and ambitious projects such as this one.

It has to start with the culture and the culture always starts with the people. You don’t have stories unless you have people. For me, it always starts with identifying the people who I feel can tell the most compelling story from perspectives and angles that don’t normally get heard from. There are a lot of big names in this film like Kanye and Pharrell, but there are lots of other people who are lesser known to the world at large that are important figures inside of grassroots hip-hop, proto-hip-hop, or what pre-dates hip-hop.

What is the motivating factor for you when seeking out those voices?

It’s [about] getting those stories and actually getting the audience closer to a feeling. Hip-hop was something that we did as kids, and [something] I was involved with before getting paid for it. So many people love hip-hop and love the culture, but I don’t think they had the benefit of experiencing it in the pure form – before there were pressures, record deals, film deals, or anything. Typically, the projects that I do with hip-hop are involved with history or important aspects of the evolution of the movement. I like to create projects that will hopefully bring people back to that feeling that will never be captured again.

Are there any influences or other films that take you back to that feeling?

It’s really hard for me to say. Not that I’m above being influenced by other films, but for me, it’s really about being inspired by people. I’ve developed a sense of identifying with them by understanding what their passions are and how their experiences can connect to the overall story that I want to tell.

Jamel Shabazz, as a documentarian and a figure, is an inspiration. He was just a guy from Brooklyn who picked up a camera and realized that it was important to capture young people of color in New York City at their best. Clothing meant so much to them, so when they were dressed in a way that made them feel good, he took these photos that captured their aura.

Knowing what a compelling and interesting character Thirstin Howl III – founder of the Lo Lifes crew – is, and that their story is largely unknown, was inspiring. To know that there was a gang that was inspired by Ralph Lauren, who did whatever they could to get those clothes, is also inspiring.

Did any of the information or history that you explored while creating this film affect your perspectives on hip-hop?

Every time I watch the film, I pick up on something new that I hadn’t before. I went in with an agenda and there were things that I knew I wanted people to touch on, but there were also themes that kept rising up without me pressing the button.

The film starts in the era of slavery and then winds up where we are today. One thing that everyone kept coming back to was the idea of freedom and how clothing, or how provocative you are with your dress, indicates how free you are. When you think about the bigger picture and where we are politically and socially, this idea of people of color and in the inner city finding some kind of sanctuary in the way they dress is very profound.

The other thing that I discovered, over and over again, is this energy and this spirit that pre-dates hip-hop. I use the example of chitlins or Soul Food. Those were scraps that the slave masters didn’t want. And what did we do? We turned them into an art form and made it our own.

Dapper Dan, the infamous designer from Harlem, did all of this amazing work with Louis Vuitton and other patterns. Those “luxury brands” weren’t thinking about half of the stuff that he designed. Nas said that he was like Tom Ford before Tom Ford. That power and sense is the same thing as the music. Hip-hop draws from so many different reference points. We’d find interesting ways to see ourselves in things that weren’t necessarily catered to or tailored for us. It’s indicative how people of color in America have survived and maintained a level of pride and dignity that translates into artistic and creative expression. The power of reimagining these other forms is one of the most important messages in the film.

What can you tell me about the film’s backers and the Sundance premiere opportunity?

The whole goal of Sundance is to obtain a distributor. The CNN part of it is cool because it’s a documentary film. The fact that a lot of people will have the ability to see it on CNN makes the endgame on this project really exciting. More people can come away with a better understanding of the conditions that created hip-hop.

This one woman in the film that was a former gang member and still lives in the Bronx neighborhood that she grew up in during the ‘60s and ‘70s, talked about how police brutality was worse then than what it is now. And this was before all of the recent things that have happened. You see footage of cops roughing people up and you see these gang members saying, “The cops are racist, it’s us against them.” Then you flash-forward to now and not much has changed socially.

But what also hasn’t changed is this determination to continue to create despite what’s going on because it’s a byproduct of our survival. What else do we have?

That’s what’s interesting about clothing, because, as Americans, many of us believe that certain items mean that we’re worth something or that we can feel better about ourselves. But hip-hop came from nothing and people took pride in making their own jean jackets, ironing on their letters, and creating their own identity. That’s always at the core of hip-hop, but with all this hyper-capitalism and this world that we live in today, it’s easy to lose sight of that purity. Hopefully, this film will help bring people back to that idea.